Venice

Imagine a city where the taxi journey from the airport so satisfies your desire for adventure, your longing for beauty, and the exhilaration of discovery, that if someone told you at the end of this thirty-minute trip you had to turn around and go home again, you would agree, quite possibly without complaint.

Imagine a city where riding the public transport system makes you feel as if you’ve achieved something lasting and profound.

Imagine a city where you can hold your phone up and point it in any direction, without framing, without adjustment, and every picture you take will be beautiful, mysterious, or both.

Imagine Venice.

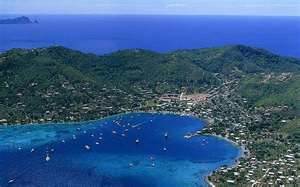

Of course, in Venice, your taxi is a speed boat, the public transport system is a series of water buses called vaporetti, and the innumerable islands upon which the city is built are thick and fast with stupendous churches, palaces, squares and canals all built to be beautiful, to impress, to showcase the might and glamour of the Venetian Empire which lasted a thousand years.

As you arrive at Marco Polo Airport at the Northern end of the Venetian Lagoon and get into your boat and start out fast through the water channel (demarcated by wooden pilings), the city shimmers before you like a mirage. You see towers, spires, domes, but they are all blurred by the haze of distance. As you come closer, the city slowly takes shape, its skyline like the plantings of some great stone garden, and by the time you pass the islands of Murano and St. Michelle, Venice is a fact, the buildings of Canareggio rise up out of the waves before you. You are astonished by this fact, no matter how many books you’ve read, or how many photographs you’ve poured over. You are astonished by the sheer unlikelihood of the place, the implausibility of a city built upon the meager islands of a salt marsh, the feat of sinking great piles and foundations beneath the waves, of constructing innumerable bridges over the waterways between the neighborhoods.

You are moving more slowly now, with time to turn your head back and forth trying to take it all in, which you can’t possibly, and then your driver turns and plunges down one of the canals and the magic overwhelms you. Plants hang from windows just above your head, you pass under bridges you could reach your hand up and touch. You peer down tiny alleyways which begin at the canal side and disappear off into the city, you look up at the slice of clear blue sky. You are moving even more slowly now, pulling to one side from time to time to let another boat pass, a gondola perhaps, a taxi, maybe a work barge.

And then, because we were staying over in the Dorsoduro, our taxi turned out into the Canal of St. Mark’s where the Grand Canal widens out into the lagoon. We crossed in front of the Doge’s Palace and St. Mark’s Square and the pastel-colored hotels, sun blazing down upon them all. And it was about this time that I decided I had achieved something profound just by getting myself here, that I had seen something that I would never forget, something that was a privilege to behold.

All through the week we spent in Venice, as we hopped on and off innumerable vaporetti, or walked through the streets and squares of the city, this feeling of privilege never left us. We were conscious of every minute of our trip being something precious, offering us beauty in every form: an ornate palace, a quiet alley, a square in sun or shade. We were conscious of being surrounded by the sea as the vaporetti wallowed in the swell or the waves beat against the quayside. We were conscious of the fragility of the place, even as its edifices towered over us: solid, ancient, imperial.

Waking up the morning after we arrived was eerie. It was Sunday and the silence of Venice was near complete. There was no roar of exhaust, no honking of horns, no screeching of brakes. There was only the sound of church bells, the cooing of pigeons, and the cries of sea gulls. There was the faint hum of a boat passing along the canal, two women speaking in Italian somewhere below us. The peacefulness of the city was a gift.

Don’t get me wrong. Venice was pulsing with people, with tourists anyway, but you could be in a square full to bursting one moment and then walk around a corner, or take a short cut through an alley, and this turn or alley would lead to a sunny square completely empty and quiet, or to a canal where there was no one, only boats bobbing quietly at their moorings, small waves sloshing over green steps leading down into the water, ancient, battered doorways secured against intruders.

The restaurants were full every night. You had to book, but when we came home at ten or eleven, walking under the soft lights along the canal, there was only the echo of heels upon cobbles, soft voices against the stone walls, and the distant sound of vessels passing between Guidecca and Dorsoduro.

To appreciate what Venice was, is and may yet be, you need to go out to the islands. You can go to the beach on Lido, or to buy glass on Murano, or to look at the multi-colored houses on Burano, but it would be better to go farther, to the island of Pellestrina full of working fishing villages, or to Torcello, where it all began.

On Pellestrina, the tourists disappear and you can walk through a quiet, deserted “normal” town, see washing hanging out of windows, hear the sounds of plates in kitchens, smell the first wafts of the noon-day meal. Venice feels a million miles away (when it’s only an hour). You remember Venice started more than a thousand years ago with fisherman and salt farmers scattered over the lonely islands of the lagoon.

On Torcello, you stare at the mosaics in the ancient basilica, more ancient than St. Mark’s, and feel the pull of the East, the power of Byzantium and how much it influenced the Venetian Empire. Torcello was the original Venice, until the harbor silted up and the salt marshes became malarial. Stone by stone, the houses were dismantled and moved south to more salubrious islands. An island, that in its heyday boasted 10,000 people, Torcello is now all but deserted.

Is that what’s going to happen to Venice? Will nature triumph over the remarkable achievements of mankind? They say Venice is sinking, or the sea is rising, or both. They’ve constructed three enormous flood gates in the lagoon to protect the city from high water. These flood gates, however, are controversial. Their deployment may keep high water from flooding the city, but it will also alter the unique aquatic environment of the lagoon. This unique aquatic environment has of course been constantly altered over more than a millennium as the ancient Venetians built up their islands, filled in the gaps between them, sailed and fished around them. Centuries of boats and people have taken their toll. Even the water taxi we took from the airport, thrilling though it may have been, is not exempt from this destruction. Its exhaust pollutes the water. Its swell damages the marine life of the shores.

Perhaps the view that drove home the fragility of the Venetian Lagoon most fully was the view from the campanile of Torcello. From its height, you can clearly see how low and flat all the islands are. You can see how little it would take to erase them from the surface of the sea.

Will Venice survive? How I hope so. How I hope I can see it again, and again, before and if it must go. In any case, I’ve brought home a little piece of Venice with me. No, not the shoes, nor the beautifully bound leather journals, but the movement, the constant up-and-down motion of the waves. I suffer, you see, from a rare condition called mal de debarquement which means that after I get off a boat, I still feel like I’m on it. This illusion of motion can last weeks, months, even years. As I sit here in my house in Connecticut, eight days after stepping off the last boat, I am still rising and falling, like a tired seagull resting upon the waves.

And I close my eyes and imagine I am on the vaporetto from Zattere to St. Mark’s, or on the ferry coming in from Torcello to Fondamenta Nove, or perhaps I’m in the water taxi approaching Venice for the first time, or watching it disappear behind me as we roar toward the airport and our plane home. Will my “illusion” last until we go back to Venice next April? I don’t know, but I feel like I’m there already, plying the waters of the Venetian Lagoon.

Bellissomo! Grazie.

Brava! I feel transported. Grazie!

Just beautiful, downright perfect writing. You capture Venice in your images, and take me right there. Thank you.

Beautiful part of the world, beautiful essay!

Beautiful part of the world, lovely essay!