Island Of the Clouds

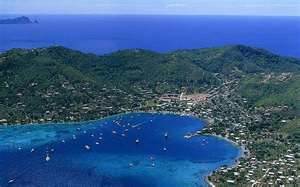

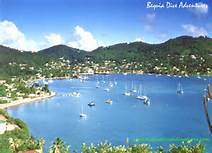

Let me just get it over with and explain where it is we are. On an island called Bequia which is one of the islands that makes up the Eastern Caribbean country of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. After the mother island, Saint Vincent, which we can see from Bequia and get to in an hour by ferry, Bequia is the largest of the Grenadine chain. She is tiny, however, only seven miles square, and treacherously mountainous. Pink and orange and not yet painted (or once painted) cinderblock homes snake up her volcanic slopes from the beaches below. Roads run up and down her mountainsides at angles that no country with snow or ice could ever dream of building. Insignificant as Bequia may seem in size, however, her harbor is a great one, known to sailors the world over. Her main bay on the Caribbean side is full of yachts and catamarans and sailboats of all sorts and on the streets of her only town, Port Elizabeth, can be heard a fair sampling of the languages of the world: English, French, German, Swedish, Italian, Norwegian and of course the local patois.

We went over to the Atlantic side today, to Spring Parish, to catch some wind. Which is not to say that there is no wind on the Caribbean side, there certainly is. The wind that comes in off the Atlantic, however, has another quality to it altogether. It is steady and insistent, bordering on vengeful and full of portent. It is the unforgiving and relentless wind that brought the explorers from Europe to the New World, that drove them inexorably towards the islands of the Caribbean carrying with them their dreams of glory and spoil and the dread diseases that would wipe out the Caribs and the Arawaks who lived here. It is here on the windward side of Bequia that you cannot help but think of these explorers as you find yourself looking for a Spanish galleon or an English caravel to round one of the deserted rocky promontories or appear in the distance on an aquamarine ocean streaked with white caps.

The parish of Spring is a parish that evokes the Caribbean past, populated today by an ever-increasing number of large ex-patriot-owned homes which echo the vanished plantations that were once imposed upon the land in the days of sugar and slaves. A few of the old plantation houses remain, but the mansions are mostly new. They hang above you as you drive the only road up to the north end of the island like gorgeous, ripe fruit which is far above your reach. They are built where it is cooler and the views are better, at the end of twisting, engine-straining roads, far away from the noise and clutter of the life lower down on the slopes.

The life of the normal people, the people that have lived here for centuries, who are now a unique mix of African and European, descendants of the population of slaves and sailors and merchants who were either brought here by force or who came here willingly to seek their fortune back in colonial times. And then there are the new people. British, Canadian, Swedish, French, American. People who may once have come into Admiralty Bay on a boat, been overwhelmed by the peace and beauty of the place, and then decided to stay. People who are running from the cold and the wet and the complications of their native countries. People who own guesthouses or restaurants or small boutiques, who have carved out a livelihood for themselves here in a small, faraway place that takes nearly a day to get to from the great centers of the world.

Then there are people like us, the people who come for a week or ten days or several months even to be able to wake up to the sounds of the waves and the birds every morning, to gaze out upon the riotous color of the gardens or just the intense blue and green of the sea and the mountains, to swim three times a day, to eat goat creole or curried conch and drink mauby, Mount Gay rum, or the local beer, Hairoun.

I am making it sound idyllic, and it is that, but it is also very real. A morning on the streets of Port Elizabeth, actually only an hour is enough, would convince you of this. You would see a working port full not just of pleasure craft, but of great hulking ferries and a tanker or two. You would see the covered markets for vegetables and fruit and twenty or more men and women set up with their smaller carts and tables of bananas, mangoes, papayas, breadfruit or cassava all along Front Street and down several of the side streets as well. You would see the hawkers of shells and bead jewelry and carved wooden boats and T-shirts. You would see the taxi stand under the almond tree where the taxis, pick-up trucks with benches and roofs to cover the passengers, congregate waiting for fares. You would see the water taxis captained by sleek, knowing young men idling near the docks, waiting to take tourists over to Lower Bay or Princess Margaret’s Beach. Down yet other side streets would be men hacking great bodies of freshly-caught tuna into steaks as a line of people with shopping bags waits patiently in the humidity and the sun. And so on. You would see the complicated lives of a population that is still mostly poor trying to wrest a living from the tourists and yacht owners who pass through here. And the music is loud and the gutters don’t always smell good and the sun and salt and humidity have played havoc with the facades of the buildings you walk past. Buildings in Port Elizabeth are more often than not in a state of in-betweenness, in between being built and being torn down, in between completion and destruction while never quite attaining either state.

And tonight is Old Year’s Night. And the music will start booming out over the beaches in the late afternoon and continue through the night into the next year. The fireworks will burst forth at midnight over the harbor, over the vessels large and small. This fireworks display is a great sight and every year we watch several smaller craft, overcome by the spectacle, fire off their emergency flares up into the explosions of color above them. Before this, however, we will sit down to table, nine British, Americans and Canadians, on a small terrace of a private home which also happens to be one of the best restaurants on the island. We will be a mix of people who come here for longer and shorter stays, some who have built homes here, some, like us, who have not, but all who come back, year after year, to this place, this island, Bequia, which has something about it which gets into your blood and doesn’t get out again. In the native Arawak, Bequia means “island of the clouds,” named no doubt for the clouds that often hang over the island and disgorge sharp, sluicing rains onto its beaches and down its slopes, but it could equally well be called “island of dreams,” for once you have been here, this island is never far from them.

Beautiful!

Sounds lovely yet you feel for the locals. Anyway Linda, enjoy your vacation.

I take your point about the unfortunate fact that the Caribbean has to rely on tourism as practically its only source of revenue, but as islands go, Bequia has escaped the worst of it. There are no large package resorts here, too small and too mountainous, and the people who come mix freely with the locals and pump a great deal of money into the local economy. Bequians have their own businesses. When I say they are ‘poor’, this is a relative statement. Some are very poor, but many manage to make a decent living. Everyone who comes here comments on the lack of conflict between locals and visitors, on the general good feeling.

I actually spent New Year’s Eve on Bequia in 1978! The only way to get to the island then was by the once a day ferry — the Friendship Rose. Everything came over on the ferry and our seats were sacks of grain and shipmates were goats and chickens! Doesn’t sound like the island has changed much!

There’s a faster ferry these days and a tiny airport, but you have to get in before sundown because there are no landing lights!

What a well written narrative describing my home away from home . Purely delightful! I love it …. When you define the current inhabitants of Bequia , possibly one other group should also be mentioned. These would be the “Red Legs”. who are the descendants of Scottish and Irish indentured workers who came to Barbados, Bequia and St. Vincent after the British Empire abolished slavery (1838) … They supplemented the pool of former slaves still working on the plantations. They performed the same type of back breaking manual labor and, in the process got sunburned and therefore, were labeled “Red Legs”.

There are still communities of these folks in Barbados, St. Vincent and Bequia. For example, the Davis , Lesley and King names are very prominent in Bequia’s Mount Pleasant area.

Thanks for that information. Very, very interesting.

Sounds glorious!! I would love to visit…now on my dream list…

Linda, what a wonderful way and place to welcome the New Year! Hope You and Tony have a happy 2013!

You two should try it some time!