Ten and Twelve Years Old

On New Year’s Day this year at around 9:30 in the morning, my husband and I were sitting in the open-air waiting room of a small Caribbean airport. It was the start of what was to be a very long day for us, traveling from Bequia, a tiny island in the Grenadine chain, back home to Connecticut. The first leg of our journey would be the flight from Bequia to Barbados via the St. Vincent and Grenadine airline SVG.

There was nothing to do once we’d checked in, and I was amusing myself by texting “Happy New Year from Bequia International!” to various people I knew, accompanying my message with a picture I’d just taken of a herd of black-bellied goats resting in the shade of a bush on the other side of the parking lot. A pig trotted past. The cooling Atlantic winds blew, and the school which lies just a stone’s throw from the airport lay quiet along with much of the nearby village of Paget Farm after the revelries of Old Year’s Night.

There were only five other people waiting for our flight, which meant that we would be island-hopping our way to Barbados to fill up the remaining seats. Three take-offs and three landings. Great. Take-offs and landings at the Grenadine island airports are abrupt and bumpy, not because the pilots don’t know what they’re doing (they’re excellent), but because the small island runways are wedged between the mountains and the sea, buffeted by the winds which are constant and ever-shifting.

If you’ve never flown on a small plane before, the first time you fly with SVG, you have to stop and take a breath. Two engines, twenty seats, a small staircase that unfolds from the back of the plane. During that first take-off, you’re grateful if you’re sitting next to someone whose hand you can squeeze. But now after more than a decade of flying with SVG, I just get on the plane. I love the feather-light feeling of lift as we rise into the air, and I’ve come to associate two strong brown arms with their hands on the throttle at take-off as one of the more comforting sights I know.

Our New Year’s flight arrived first as an approaching buzz in the sky and then as an actual plane when it touched down and sped over to the tiny terminal. Our small group of travelers got up, were invited to step over the luggage scales, and exited the terminal through the service door. The bags went into the back hold, and we took off a few minutes later. Paget Farm fell away beneath us as we flew along the Atlantic coast of the island, past Friendship Bay, and then on to Mustique and south to Union. We got to Barbados fifty minutes after leaving Union, waited four hours to connect to the New York flight, and walked into our house in Connecticut at ten minutes after eleven.

Three days later, another plane lifted off from Bequia International. They left only an hour or so after we did, at midday, bound for St. Lucia, 60 miles to the north. It was a very different sort of plane from the one we were on. It was a privately owned single-engine aircraft painted with bright green camouflage stripes that weren’t meant to hide it from anyone and a set of bared teeth over its nose. Anyone who spent time in Bequia knew this plane. It was often parked on the Bequia runway though I’m sure I saw it somewhere else this year, on the tarmac in Barbados or Mustique or on Union Island.

It belonged to an American man who had lived for forty years on Bequia. He chartered his plane for people who didn’t feel like waiting around for the scheduled SVG flight, or who didn’t want to fly over to St. Vincent or Barbados to catch a more frequent service, or just people with money who thought flying in a plane like his would be cool. His passengers on January 4th were a father and his two daughters. The father was an actor who’s been in movies people have heard of. He had his daughters with him for the holiday, ten and twelve years old.

The residents of Paget heard the engine die shortly after take-off: men and women out in the noon day sun, fishermen returning with the morning’s catch. They heard the engine splutter back to life only to die again a few moments later. A good friend of mine, a pilot, explained that as long as you have lift, you can fly a plane for quite some time without a functioning engine and bring it down safely, on land or on sea, but that isn’t what happened last Thursday. “Maybe the wind got him as he was trying to turn back,” she suggested although I could tell that she felt uncomfortable with this explanation. He’d lost lift awfully quickly, she said. She didn’t really understand it.

And she most likely never will. Shortly after the engine died for the second time, the plane plummeted headfirst into the sea.

The fisherman who watched the pilot lose his struggle to stay aloft turned their boats around and rushed out to where the plane had gone down. Everyone knew whose plane it was. Many of them had worked for him, or been trained by him. He’d also been a diver. They dove on the wreck and brought the bodies up. They found them all still strapped into their seats. The pilot, the father, and his two daughters, ten and twelve years old.

The island went into shock. Despite the tiny runways and often challenging flying conditions, small plane crashes are rare in the Grenadines, though Bequia had known another. Thirty years ago, in November of 1994, the owner of Mac’s Pizzeria, a local, much-loved Bequian, was killed in another single-engine plane crash trying to take off from nearby Saint Vincent airport.

It was a question of lift that day too, lift fought for, but not sufficiently achieved. That plane crashed on land and exploded. All were killed. Mac’s widow, who, unimaginably, lost both her father and husband on that dreadful day, continued to run Mac’s Pizzeria on her own. She eventually remarried, and, heroically, got back into a single-engine airplane with her second husband. She posted a blog about flying a few days ago. She didn’t mention what had just happened. But she did say, in a quiet nod to the tragedy perhaps, or to what people might have started saying about it, that she’d never have gone to or seen many of the places she had if she hadn’t flown in a single-engine plane.

People make decisions about their lives. They calculate risks and live, or not, with the consequences of these decisions. Children, however, live with the consequences of the decisions their parents make for them.

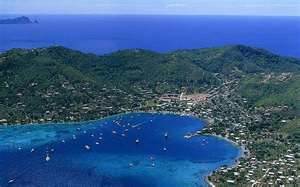

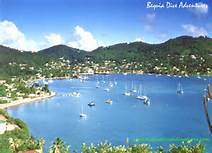

Don’t misunderstand me. The father’s decision to take his daughters to Bequia for the holidays must have been delightful for them. They were seen repeatedly at the Plantation, a small hotel in Port Elizabeth, Bequia’s only town. The Plantation looks out over an idyllic harbor full of boats to the green hills of Hamilton on the other side with its candy-colored houses.

On Old Year’s Night, as New Year’s Eve is called down there, people sail into this harbor from all over the Caribbean. At midnight, the boats, bobbing like Christmas decorations on the water, blow their horns in unison, and then a stupendous display of fireworks erupts into the sky. People throng the walkways and docks, pressed up against one another, watching the display in wonder. I can imagine how much the two young girls loved this night, and I’m sure that four days later they were excited to fly in a plane that looked like something they might see in one of their father’s movies.

One can’t help but think about the moment that this excitement turned to dread, or wonder what their father shouted to them as the plane began to drop, that they would be okay, perhaps, or that he loved them, or both. Or did he not have time to think that clearly? “It would have been quick,” my pilot friend told me. There would have been a terrible moment of clarity, and then it all would have ended very fast.

Too fast? Or not fast enough?

A group of men who’d been working in Paget when the crash occurred, downed tools for the day and went home to their families, in particular to their children, who they kept close at hand. The Bequia men who brought the bodies up handed them over to the Saint Vincent Coast Guard that was going to bring them to the morgue in Saint Vincent for autopsies. The news spread quickly across the island, the pilot’s family was notified, and I don’t know who the unlucky individual was who had to make the call to California to tell the mother of the girls.

I think of myself at ten when I flew for the first time, on carriers that no longer exist and from an airport my mother still sometimes called Idlewild. I remember how excited I was. It was an expensive trip for our family, something my parents had to save a long time for. We, too, chose an island, Bermuda, and to be frugal stayed in an efficiency apartment out in Somerset, a place that I asked about when I returned to Bermuda forty years later, but which I couldn’t find, and which no one I spoke to could remember.

As no one will remember this tragedy, except for the families and friends it devastated and the islanders whose history it darkened. Larger catastrophes will pull it under like great waves devour smaller ones on the beach. But I’ll remember. I’ll remember the two little girls who took off from the same quiet airport I did where the goats grazed and the Atlantic breezes blew, the girls who spent a fairy tale vacation in the Caribbean with their father, and then fell into the sea, ten and twelve years old.

So sad, Linda. Thank you for writing this.

I have a few tears after reading this. People here on Bequia, now after a bit of time , are still very sad about this tragedy.

I shed quite a few tears writing it.

I saw it on the news and said a prayer for the family.

As did so many.

Heart wrenching, Linda. But a lovely, sensitive take on a family tragedy.

Very sad family tragedy. I also appreciate your sensitivity in writing this story. May God comfort the family in this difficult time.

So touchingly written: brought to life a story that had only been a blip when I read about it earlier this month. You made it so personal. Thanks for bringing it to life, Linda.